Write TCP/IP Stack by Yourself (3): TCP Three-Way Handshake

Data Structures

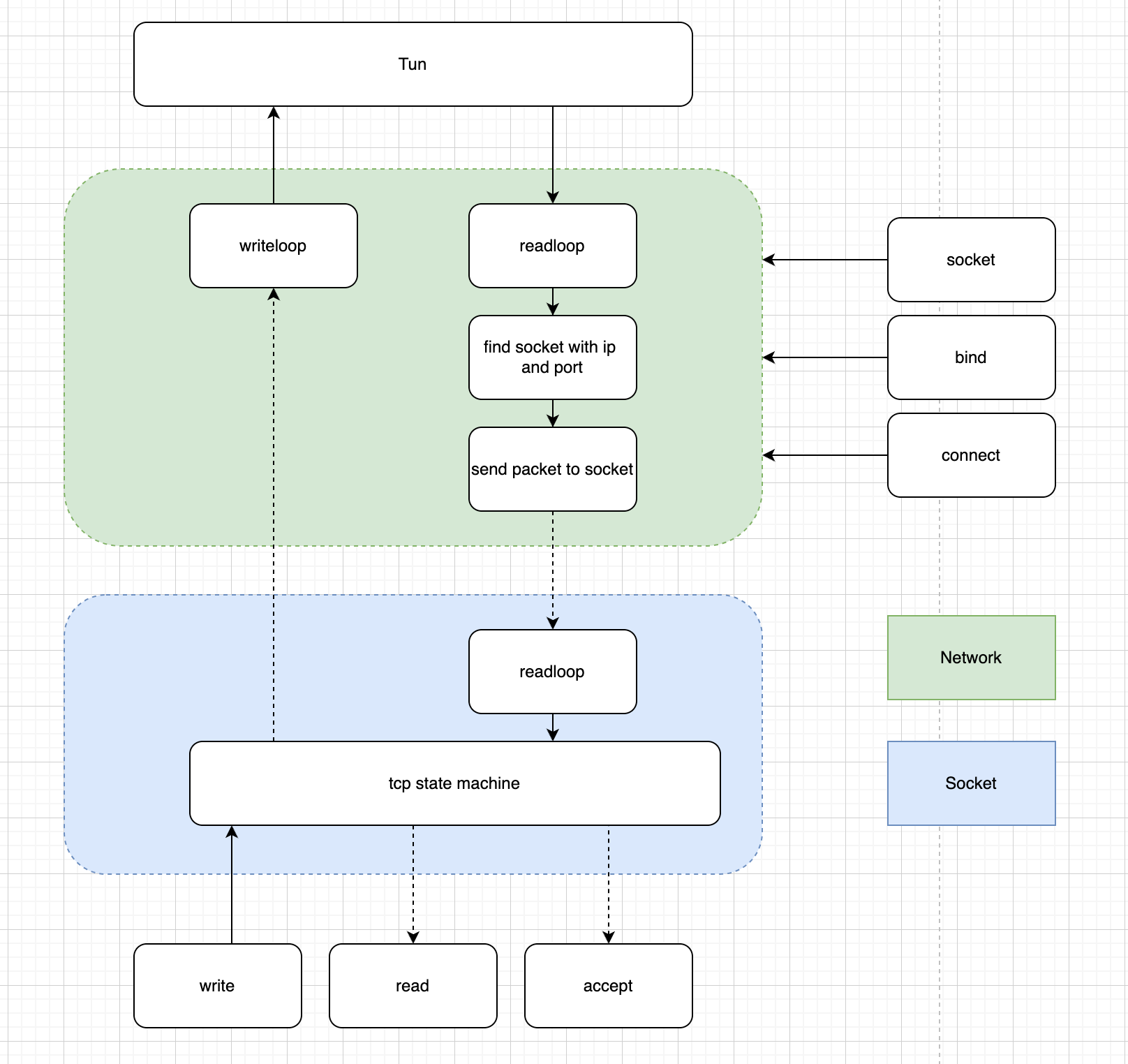

The main data structures of the project and their interactions are shown in the following diagram:

- Dotted arrows represent asynchronous calls, implemented using Go’s channel mechanism. If you want to implement this in another language, you’ll need to use a thread-safe message queue to replace the channels.

Networkis mainly responsible for reading data packets from TUN, writing to TUN, binding socket and IP port information, and routing network packets to the appropriate socket for processing based on IP port information.Socketimplements TCP protocol’s connection management, data sending and receiving.- When you send a SYN request to TUN, the data packet flow is:

tun -> Network -> Socket(handle syn) -> Socket(send syn ack) -> Network -> tun - After the connection is established, when sending data through the write interface, the packet flow is:

Socket(send data) -> Network -> tun

Three-Way Handshake and Four-Way Handshake

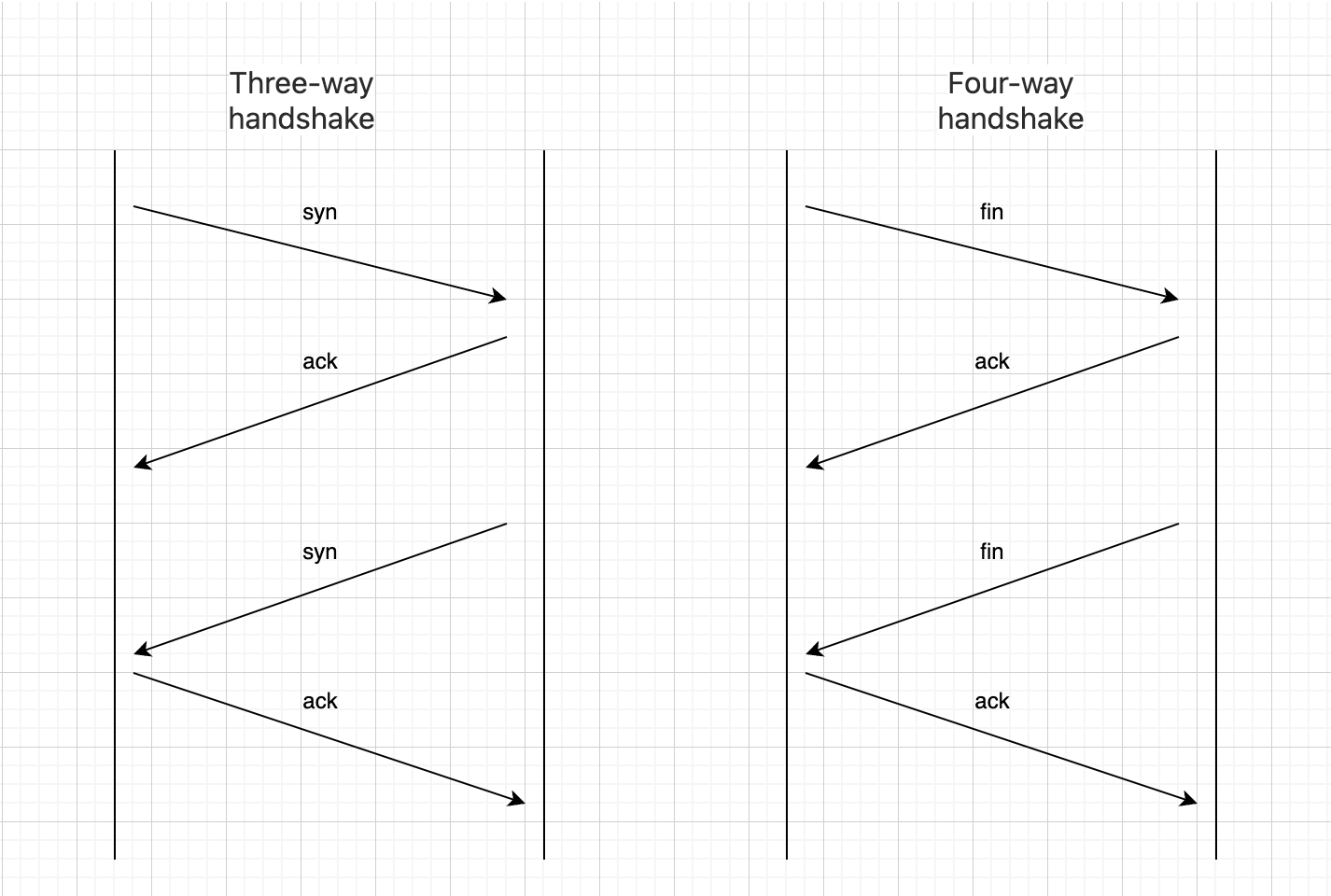

You might find that the three-way handshake and four-way handshake processes are easy to forget, and the details during the handshake are unclear. Here’s a simple approach to help you understand the handshake process. In my understanding, there are two key points in TCP design:

- Every sent data message requires an ACK response from the other party. This includes data packets, SYN, FIN, etc.

- TCP connections are full-duplex, so establishing a connection requires both parties to confirm receiving the other’s information. A connection with only one party confirming is an intermediate state, called a half-open or half-closed connection.

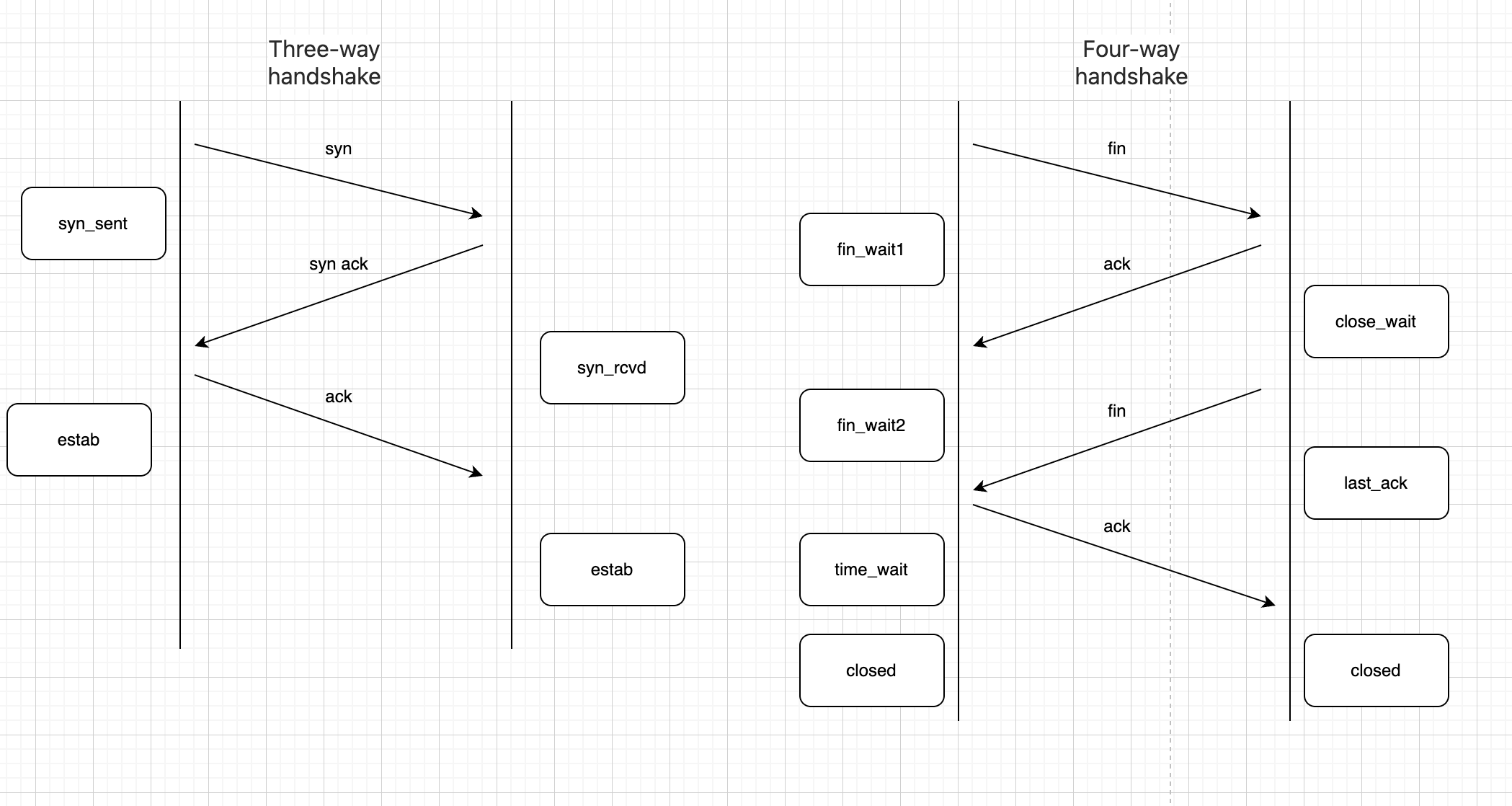

Understanding these two points, you’ll see that the three-way handshake and four-way handshake processes are actually identical, just that the handshake sends SYN while the closing process sends FIN. It looks like this:

You might wonder, wouldn’t this make the three-way handshake into a four-way handshake? This is because the designers combined the server’s SYN and ACK packets into one packet to improve performance, turning it into a three-way handshake. During connection termination, the server might still have data to send, so it can’t combine FIN and ACK, resulting in a four-way handshake. The final process looks like this:

Sequence and Acknowledgment Number Calculation

Sequence and acknowledgment numbers are another challenging aspect of the TCP protocol. In my understanding, you only need to remember one point:

- All individual data messages occupy one sequence number and one acknowledgment number. Data messages include data packets, SYN, FIN, etc.

For example:

- During the three-way handshake, after sending the first SYN, the SYN occupies one sequence number, so the next packet from the client must use seq+1 as the sequence number. This means the first data packet’s sequence number must be the initial sequence number plus 1.

- During the four-way handshake, after sending the first FIN, the FIN occupies one sequence number, so the next packet from the client must use seq+1 as the sequence number. For the server, after receiving FIN, if it only sends an ACK (ACK is not a data message), then the server’s next packet will still use the current sequence number, no need to add 1.

- For data packets, each byte of data occupies one sequence number. If you send n bytes, the subsequent sequence number increases by n.

The acknowledgment number can be remembered in relation to the sequence number, simply as the next sequence number the other party should send. So calculating the acknowledgment number becomes calculating what sequence number the peer should send.

Relationship between Send Window, Receive Window, and Sequence/Acknowledgment Numbers

Understanding sequence and acknowledgment numbers is crucial for understanding the sliding window. Here are the sliding window parameters defined in the RFC:

|

|

Translated:

- SND.UNA: The sequence number of sent but unacknowledged data

- SND.NXT: The next sequence number to send, all data before this number has been sent

- RCV.NXT: The next sequence number to receive, all data before this number has been received

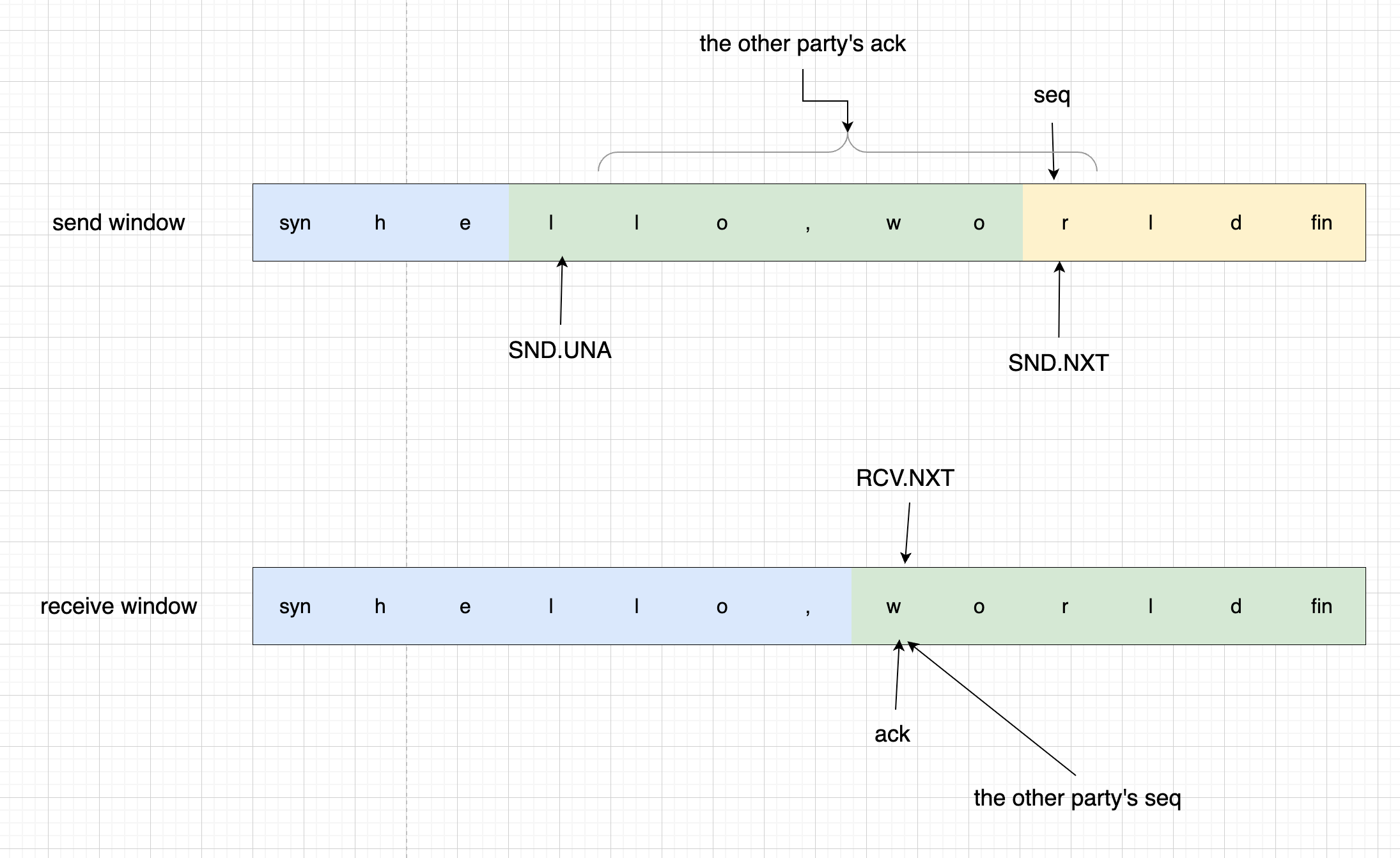

Looking at our earlier analysis of sequence and acknowledgment numbers, SND.NXT is our next sequence number to send, and RCV.NXT is the acknowledgment number. Let’s look at a diagram:

Notice that I’ve included SYN and FIN in the data boxes. Although they’re not real data, they occupy sequence numbers, so including them in the data boxes makes it easier to understand.

Looking at the diagram, we can calculate the sequence and acknowledgment numbers the other party should send. Our acknowledgment number is the next sequence number the other party should send, and the other party’s acknowledgment number is the next sequence number we should send.

However, the other party might not have received all our data, so their acknowledgment number might be smaller than our SND.NXT, it’s a range. The other party shouldn’t acknowledge the same data repeatedly, so their acknowledgment number range is (SND.UNA, SND.NXT].

Note it’s greater than SND.UNA because the acknowledgment is the next sequence number to send.

socket()

The socket() interface creates a socket object. Currently, we can only create TCP sockets, while the Linux kernel can create sockets for UDP and other protocols.

Here’s the socket object implementation:

|

|

Key fields to note:

- synQueue: The famous half-connection queue, used to store sockets that have received SYN but not ACK packets. Interestingly, it’s a

maphere - acceptQueue: The famous full-connection queue, used to store sockets with established connections. Here it’s a

channelfor asynchronously passingsocketto theacceptinterface - recvNext: Next sequence number to receive

- sendNext: Next sequence number to send

- sendUnack: Sequence number of sent but unacknowledged data

- sendBuffer: Send buffer for storing data to be sent

Half-Connection Queue

The name suggests it should be a queue, but thinking carefully, half-connections don’t receive the third handshake in first-in-first-out order, so why would it be a queue? Moreover, to find which half-connection received the third handshake, we clearly should use a map for storage.

I once tried to find the half-connection queue implementation in the Linux kernel source code, but the kernel code was convoluted with no explicit syn queue. It was quite confusing until I found the answer on Stack Overflow:

confusion-about-syn-queue-and-accept-queue.

In short, the kernel doesn’t have an explicit half-connection queue data structure. The functionality is carried by a hash table called ehash, which isn’t specifically designed for half-connections and has other functions.

The full-connection queue does have a dedicated variable icsk_accept_queue.

bind()

The bind() interface binds a socket to a specified IP and port, specifically using a map in Network to associate SocketAddr with TcpSocket.

|

|

|

|

The socket retrieval method is quite sophisticated. The logic is:

- First try to get the socket with key

[localIP, localPort, remoteIP, remotePort]. If successful, it’s either an established connection or a socket that initiated the connection - If not found, try with key

[localIP, localPort]. This would be a listening socket - If not found, try with key

[localPort]. This would be a socket listening on0.0.0.0

I haven’t implemented the third logic, but it’s straightforward to do so. Using this technique, our bind can handle all types of sockets flexibly.

listen()

The listen() interface sets the socket to listening state. Implementation:

|

|

Main logic:

- Initialize socket data, note that

acceptQueue’s length ismin(backlog, s.network.opt.SoMaxConn) - Start a goroutine (other languages would use threads, processes, or other concurrency mechanisms) to monitor

writeCh. When data arrives (fromNetworkreading fromTun), call thehandlefunction to process it handleis responsible for locking, callinghandleStateto generate response packets, then passing response packets toNetwork

The design of handle and handleState functions is worth mentioning:

- The internal processing of

handleStateis very pure, not involving locks, channels, or other complex concurrency mechanisms. This pure logic is preserved for easy unit testing. Ideally,handleStateshould be side-effect free, only returning results based on input parameters (called a pure function). - Putting the lock at the outermost layer also makes the logic clearer, otherwise it’s very easy to cause deadlocks, data races, and other concurrency issues.

Three-Way Handshake

Actually, implementing a usable three-way handshake and four-way handshake process just requires understanding sequence and acknowledgment number calculation, and send/receive window calculation. With the above foundation, implementation becomes relatively straightforward. The protocol handling entry point is written like this:

|

|

The entry point is quite straightforward, just two big switch statements that call different handling functions based on the current connection state. Let’s analyze these handling functions one by one.

Handling SYN Packet in Passive Open

Since there’s no socket listening on [localIP, localPort, remoteIP, remotePort] when the SYN packet arrives, the SYN packet is handled by the socket listening on [localIP, localPort]. The handling logic is:

|

|

Main logic:

- Verify sequence and acknowledgment numbers are correct. This is a common logic placed in the

checkSeqAckfunction - Set connection state to

tcpip.TcpStateEstablished - Set

sendUnackto the peer’s acknowledgment number, as the peer sent ACK indicating they received the SYN - Remove current socket from

synQueue - Add current socket to

acceptQueueas the connection is established. IfacceptQueueis full, drop the connection and return directly - Add current socket to

Network, listening on address[localIP, localPort, remoteIP, remotePort]. This address takes precedence over the listener’s[localIP, localPort], so subsequent requests will be handled by the current socket

connect()

This is actively opening a connection. Implementation:

|

|

Main logic:

- Bind socket to

[localIP, localPort, remoteIP, remotePort]. IflocalIPandlocalPortwere specified during bind, use those; otherwise use randomly allocated ones fromNetwork - Initialize socket, setting itself as its own

listener

Let’s look at the Socket.connect() function:

|

|

Main logic:

- Set connection state to

tcpip.TcpStateSynSent - Send SYN packet

- Block to get a socket from

acceptQueue. The socket obtained will be the current socket, with the listener being the socket itself. The current socket listens on[localIP, localPort, remoteIP, remotePort], there will only be one socket

Other logic is the same as handling SYN packet in passive open, as they are symmetric.

Handling SYN+ACK Packet in Active Open

Implementation: handleSynResp

|

|

Main logic:

- Verify it must be SYN+ACK packet

- Verify acknowledgment number is correct. Since only SYN was sent, acknowledgment number must be

sendUnack+1 - Set connection state to

tcpip.TcpStateEstablished - Set

recvNextto peer’s sequence number plus 1, as peer’s SYN occupies one sequence number - Set

sendUnackplus 1, as peer sent ACK indicating they received the SYN sendNextdoesn’t change as we only sent ACK, no data sent

accept()

The accept function simply blocks to get a socket from acceptQueue, very simple implementation:

|

|

Summary

Finally, we’ve covered the three-way handshake. The three-way handshake has many details, but understanding sequence and acknowledgment numbers, and send/receive window calculation makes it relatively easy to understand. My implementation is just a toy implementation of the three-way handshake. Production-level implementations are much more complex. There are also many valuable topics in this article that we haven’t expanded on, such as how thread safety is implemented and how to make the code more testable. I’ll discuss these in separate articles later. If you found this article helpful, please give it a like and follow me. Feel free to point out any errors. Also welcome to star my experimental project lab and follow my GitHub page qianz.